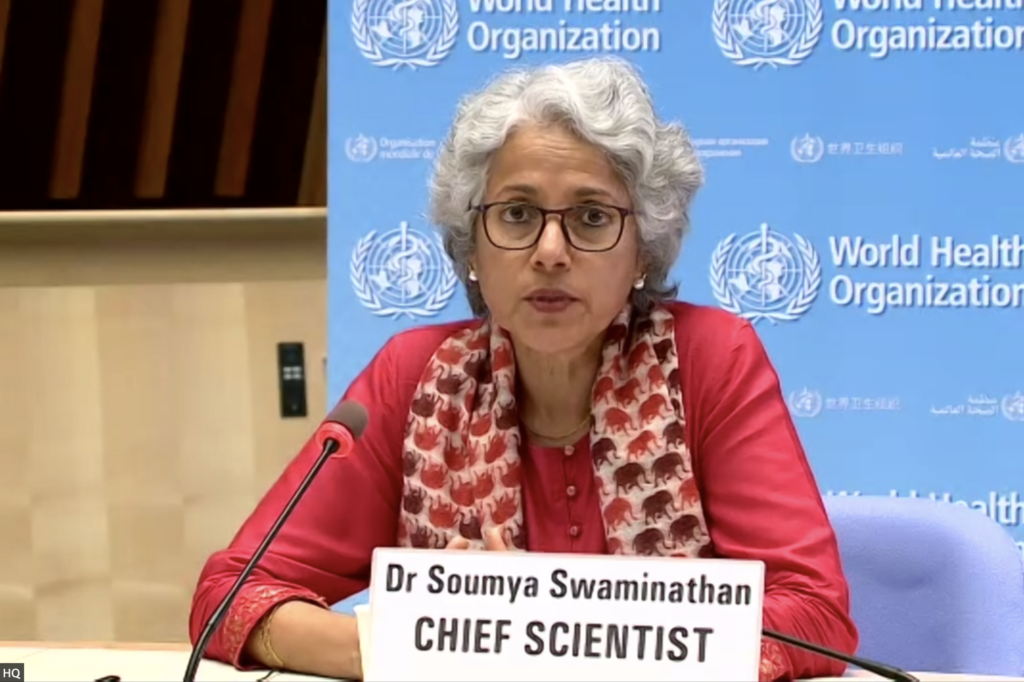

New Delhi: Former World Health Organisation (WHO) chief scientist Soumya Swaminathan has suggested installing air purifiers in all government and private schools to protect children from hazardous air pollution in cities like Delhi. In an interview with PTI, Swaminathan, who is the advisor to health ministry, said India has gathered enough data on air pollution and it is now time to take action.

“Children are disproportionately impacted because they tend to breathe faster. They have a higher respiratory rate than adults. They are also shorter, closer to the ground, and a lot of these pollutants actually settle down. They are growing and therefore all their organs are impacted.

“So definitely, I think that air purifiers, if available and affordable, can be or should be used. Certainly, we could think of putting them in all schools because children spend a lot of time there. Whether government or private schools, if we could improve air quality within schools, that will benefit children. But the final solution is, let’s clean up the air,” she said.

Delhi often sees hazardous air quality levels in winters requiring strict restrictions under stages 3 and 4 of the air pollution control plan called GRAP, which significantly disrupt the education system and affect learning quality.

After the Supreme Court aired concerns over learning loss, the Commission for Air Quality Management in November last year directed schools and colleges in Delhi-NCR to shift classes up to 12th standard to a “hybrid” mode in case of high air pollution levels.

According to a report published on Tuesday by Swiss air technology company IQAir, six of the world’s 10 most polluted cities are in India, with Byrnihat in Meghalaya topping the list.

The World Air Quality Report 2024 also said Delhi remains the most polluted capital city globally, while India ranked as the world’s fifth most polluted country in 2024.

Air pollution in Delhi has worsened, with the annual average PM2.5 concentration rising from 102.4 micrograms per cubic metre in 2023 to 108.3 micrograms per cubic metre in 2024.

Overall, 35 per cent of Indian cities reported annual PM2.5 levels exceeding 10 times the WHO limit of 5 micrograms per cubic metre, the report said.

Asked if implementation is the missing key in the fight against air pollution, Swaminathan said: “We have the data now, I think what we need is the action.”

Some low-hanging fruits include replacing biomass with LPG and providing more subsidies for poor families, especially women, as it benefits both health and air quality, the former director general of ICMR said.

“The first cylinder is free, but the poorest families could be given an enhanced subsidy, for women in particular,” she said.

Under the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY), the government provides free LPG (liquefied petroleum gas) connections to women from below-poverty line households. However, high refill costs, even with subsidies, have made domestic gas cylinders less affordable for rural and deprived families.

Swaminathan said cities should expand public transport, impose fines on excessive car use and strictly enforce industrial pollution laws. “Both incentives and disincentives would have to be used.”

She suggested exploring innovative ideas like “no-car zones” and a massive expansion of public transport, including e-buses, metro and cycling lanes, similar to measures taken in Beijing, which has significantly reduced air pollution.

Swaminathan, who is also the co-chairperson of Our Common Air (OCA), a global commission launched by Clean Air Fund (CAF) in London, said strict enforcement of laws and regulations is crucial.

“We already have laws and regulations for emissions from industry and construction, etc. Make sure that the industries are actually abiding by those regulations and they put in place certain equipment to reduce the emissions… that they are taking shortcuts,” she said.

Asked about the impact of overlooking PM2.5 while measuring progress under the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP), she said PM2.5 is “definitely the most harmful pollutant” because it enters the bloodstream through the lungs and spreads throughout the body.

“It affects the brain, heart, and pancreas, increases the risk of diabetes, and even enhances dementia in young children. Children who live in more polluted areas, their learning is impacted. It also affects pregnant women, leading to smaller babies with smaller lungs,” she said.

The NCAP, launched in 2019, aims to reduce particulate pollution by 40 per cent by 2026, using 2019-20 as the base year. However, in practice, only PM10 concentration is being considered for performance assessment.

While India has improved air quality monitoring, Swaminathan said the NCAP should take an “airshed approach” rather than focusing only on cities, as pollution in places like Delhi comes from surrounding areas too.