Field Notes from India: Climate Adaptation from the Ground Up

Two days with climate educators in Ahmedabad, India changed my understanding and appreciation of climate resilience.

I spent last week in New Delhi, participating in the conference, India 2047: Building a Climate-Resilient Future. Academics, civil society, and government officials were divided into groups focusing on science, health, labor, and the built environment. It was fascinating to explore the daunting challenges India will face as many of its regions confront daily temperatures well over 100 degrees.

The two days spent before the conference, though, were even more fascinating and personally meaningful. Discussing climate change at a large workshop can provide important policy insights and opportunities for networking, but it necessarily lacks the human element. Discussions and presentations in a conference center cannot adequately capture what people are doing on the ground.

This blog describes the remarkable innovations I learned that poor communities in India are putting in place today for climate adaptation. These are led by women workers who earn $100-$150 dollars a month, much like half of the world’s population. What follows is paraphrased from discussions with members of the Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA).

SEWA was founded in 1972. It now has a membership of over 3.2 million poor, self-employed women workers. Indeed, 93% of the Indian labor force are so-called “informal workers,” comprising everything from small farmers and vegetable sellers to piece-work stitching and waste recyclers. They largely work in their crowded homes (sometimes just 8’x8’), on small plots, or on the street. They have neither employers to provide benefits nor political parties to represent their interests. In its first 50 years, SEWA has become well known for organizing and for financial innovations that enable poor women to enjoy employment and self-reliance by building their bargaining power and facilitating access to credit and their own bank accounts, giving them control over assets, the first step out of poverty.

SEWA was founded in 1972. It now has a membership of over 3.2 million poor, self-employed women workers. Indeed, 93% of the Indian labor force are so-called “informal workers,” comprising everything from small farmers and vegetable sellers to piece-work stitching and waste recyclers. They largely work in their crowded homes (sometimes just 8’x8’), on small plots, or on the street. They have neither employers to provide benefits nor political parties to represent their interests. In its first 50 years, SEWA has become well known for organizing and for financial innovations that enable poor women to enjoy employment and self-reliance by building their bargaining power and facilitating access to credit and their own bank accounts, giving them control over assets, the first step out of poverty.

In 2021, as the leadership team started planning over how to best celebrate SEWA’s 50th Anniversary, the founder challenged them to understand how SEWA can stay relevant to the grassroots women workers for the next 50 years.

The team held focus groups with its members and, to their surprise, the younger members said that to stay relevant for the next half century SEWA had to focus on environmental protection. Out of this emerged the “Swaccha Akash” campaign – building cleaner skies for future generations. SEWA members in Gujarat, a state in Northwest India with the largest SEWA membership, took the lead in the Building Cleaner Skies campaign with a series of initiatives “increasing awareness about the climate shocks and its effect on the members, understanding the adaptation and mitigation measures taken by the members, scaling up the adaptation and mitigation initiatives, enabling financial linkages and policy interventions.”

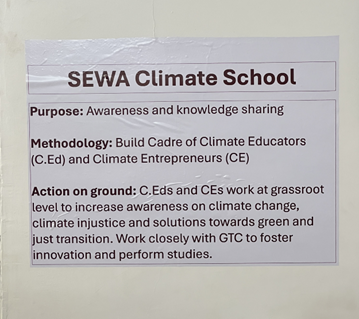

The first goal of the campaign was to create awareness about climate change. As a SEWA member described to me, “there is a lot of misconception about climate change. People are still saying that they are doing something wrong, so God is punishing them.” To address this, SEWA created the Climate School. This required developing content on climate science in a way that can be understood by people who have not gone very far in school. Terms such as global warming and carbon emissions must be converted into everyday language. Content was also developed to share innovative solutions like precision irrigation, like biogas digesters, like cooling roof paints or cooling shelters.

Once the content is created, though, how is it disseminated? The Climate School trains Climate Educators. Twenty-eight young women were selected from 14 districts around Gujarat. Over six months, they split their time between learning at the school and in field training. Most of these women have studied only up to 7th or 8th grade and have never left their homes, so they must be taught interpersonal skills. They also receive training on digital and financial literacy “because if the member asks what about the payment, how can I buy it, how do I afford it, she should be able to explain.”

Once the content is created, though, how is it disseminated? The Climate School trains Climate Educators. Twenty-eight young women were selected from 14 districts around Gujarat. Over six months, they split their time between learning at the school and in field training. Most of these women have studied only up to 7th or 8th grade and have never left their homes, so they must be taught interpersonal skills. They also receive training on digital and financial literacy “because if the member asks what about the payment, how can I buy it, how do I afford it, she should be able to explain.”

The Climate School thus first creates content, trains Climate Educators, and then Trains Climate Entrepreneurs. This group of women learns about specific adaptation technologies. Once the Educators generate interest in biogas instead of cook stoves or drip instead of flood irrigation, “if I’m a member and I’m convinced that I need to adopt these adaptation or mitigation solutions, so now how do I do it? There are no shops in the village where I can just walk and buy. Even if there is a shop, there are so many models. Which is affordable? Which is going to satisfy my needs? For that there comes the Climate Entrepreneur.”

The Entrepreneur is trained to help the households understand their costs for energy or water and recommend specific products that have been vetted by SEWA and favorable prices negotiated. Importantly, Entrepreneurs also help her in accessing loans and all the documents required.

Because SEWA members generally earn less than $150 per month, SEWA has created the Livelihood Recovery and Resilience Fund. Given their limited earnings, most of SEWA’s members do not have any collateral; thus they have no access to credit. The Fund is an innovative financing solution that serves several purposes. First, it provides contingency funds to members in the event of a climate shock. Even if there is government relief, it can take three to four months to come in, but a member needs immediate funds to get back on her feet and restart her livelihood. The Fund provides money to the member within 15 days of the climate shock so that members can restart their livelihoods, and when the government relief comes in or her livelihood stabilizes then she repays that back. Because it is interest free, it operates as a revolving fund rather than a bank, which avoids regulatory compliance costs.

Amazingly, the Fund has had zero defaults. As it was described to me, “there has been zero default because members understand that, when I was in difficulty I got it, and if I will not repay then next time when there is a climate event, I will not get it.”

The second objective of is to facilitate entry of members into formal financial systems. Most members have no collateral, but they can build a credit history when they repay the Fund. Next time she needs a loan, she will not need a guarantee. She will be directly eligible for development for private and public sector.

And how does the Fund get its money? There are multiple sources. In addition to philanthropic grants, all SEWA members contribute one day of wages per month.

This is an oversimplified explanation of a series of nested programs, but the point should be clear. Creative and important innovations to address climate shocks are taking place in the field, far from government offices and conference halls.

I found the SEWA discussions inspiring. They brought a personal and community voice to what, so often for lawyers and policy makers, are technical discussions focused on cost benefit analyses, risk assessments, or treaty negotiation. These have their place, to be sure, but my time in Ahmedabad brought home the central lesson that people are problem solvers. The Climate Educators and Entrepreneurs will not cure climate change, of course, but these young women provide an important window into the creative local resilience strategies being developed out of necessity around the globe.