[ad_1]

New Delhi: India is at a critical juncture in its mission to eliminate malaria, with tribal and hard-to-reach regions posing the final and toughest challenge. In an insightful conversation, Dr. Sita Rama Budaraja, Advisor, Health, Tata Trusts, discusses with Rashmi Mabiyan Kaur, Principal Correspondent at ETHealthworld, how strengthening primary healthcare through Ayushman Arogya Mandirs, preparing for the malaria vaccine rollout, leveraging digital innovations, and embracing cutting-edge genetic research are shaping India’s roadmap to a malaria-free future. He underscores that addressing healthcare gaps in marginalized communities, while building trust and resilience into systems, is key to achieving malaria elimination by 2030.

Where does India stand in its fight against malaria today?The concept of the ‘last mile’ is particularly pertinent to India’s malaria elimination efforts. Despite significant progress, most malaria-related illnesses and deaths still occur in remote, tribal, and forested areas. These regions continue to have limited access to timely and quality healthcare, making this final stretch in the fight against malaria both the most difficult and the most important. However, efforts such as strengthening the primary healthcare system through Ayushman Arogya Mandirs (AAM) are improving healthcare delivery. These centers are helping improve healthcare services at the local level by bringing essential diagnosis, treatment, and prevention closer to communities that need them most.How do you see the integration of malaria services into existing primary healthcare systems evolving, especially under the Ayushman Bharat Health and Wellness Centres framework?

Ayushman Bharat Health and Wellness Centres, now renamed Ayushman Arogya Mandirs (AAMs), have been set up to deliver 12 essential primary healthcare services, including the prevention and control of communicable diseases. In this setup, integrating initiatives that emphasize locally endemic diseases such as malaria is very important, particularly in areas where the disease is widespread. In such regions, early detection, timely treatment, and preventive measures will be key priorities. Strengthening the role of frontline health workers, ensuring a steady supply of diagnostic tools and antimalarial medicines, along with increasing community awareness, are all important steps in making malaria care more accessible through AAMs.Tata Trusts has been involved in strengthening health systems. How central is primary healthcare in the roadmap to malaria elimination, especially in tribal or hard-to-reach areas?

An effective primary health system is crucial for ensuring community well-being and achieving equitable health outcomes. A strong foundation in primary care can deliver long-term benefits across the population. Tata Trusts’ healthcare portfolio has consistently focused on strengthening primary healthcare and health systems, both in urban centers and in hinterlands across the country, while actively supporting government efforts to build resilient and responsive healthcare infrastructure. In Madhya Pradesh, Tata Trusts is supporting the state government in bolstering 500 selected Ayushman Arogya Mandirs (AAMs) to effectively deliver the 12 essential components of primary healthcare, as envisioned under the National Health Mission. The objective is to develop these AAMs into model centers of comprehensive primary care. In Odisha, the state with the highest incidence of malaria cases, the Trusts supported the state government in ensuring early detection and treatment of malaria in selected tribal pockets. This focused intervention has led to a significant reduction in the disease burden across the project areas.

What challenges persist in early diagnosis and treatment of malaria at the primary care level, and how can these be addressed through better workforce or technology support?

Key challenges in early diagnosis and treatment of malaria at the primary care level include delayed detection, limited human resources, and inadequate medical infrastructure, particularly in remote areas. Access to emergency healthcare for severe malaria cases, such as cerebral malaria, renal complications, and anemia in pregnant women, remains a significant barrier. To address these, strengthening Ayushman Arogya Mandirs (AAMs), enhancing diagnostic capacity, and improving emergency transport systems are critical. Targeted efforts involving key stakeholders and public-private partnerships (PPPs) can further aid surveillance, continuous reporting, and deployment of trained personnel in remote areas.

India is closely watching the rollout of the RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine in Africa. How do you see the malaria vaccine fitting into India’s broader malaria elimination strategy, especially in high-burden states like Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Jharkhand?

The RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine targets Plasmodium falciparum (P. falciparum), the parasite that causes the most severe and often fatal cases of malaria. In India, P. falciparum is the most common strain found in tribal and forested regions, especially in high-burden states like Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Jharkhand, areas that still face major challenges due to limited access to healthcare. Given these conditions, the vaccine could be a valuable addition to India’s malaria control efforts. It has the potential to be effective in these high-risk regions if included in the national immunisation programme.

How can digital health tools be leveraged to monitor vaccine coverage, track outcomes, and flag gaps in real-time?

Digital health tools offer significant potential to enhance malaria control efforts. By integrating real-time data systems, we can track vaccine coverage, monitor treatment outcomes, and identify geographic or demographic gaps quickly. Portable microscopes to test for suspected cases of malaria and mobile-based platforms can support frontline workers in capturing and uploading data at the point of care, while dashboards can enable timely decision-making at district and state levels. Tata Trusts has piloted three distinct digital health models, each demonstrating promising outcomes. In Andhra Pradesh, a hub-and-spoke telemedicine model was implemented to improve rural healthcare access, reaching villages around Vijayawada. In Uttar Pradesh, the Trusts partnered with NGOs such as Ramakrishna Mission Hospital in Vrindavan and Varanasi to support grassroots digital health initiatives. In Telangana, a joint venture with the state government was successfully scaled and evolved into a sustainable program. The experiences from these projects can be leveraged by the government in strengthening the supply chain tracking systems, improving accountability, resource allocation, and program responsiveness—ultimately contributing to more efficient and equitable malaria surveillance and intervention delivery.

Looking ahead, what kind of policy and operational groundwork should India lay now to be malaria vaccine-ready in the coming years?

In the coming years, India’s malaria vaccine strategy should focus on areas where Plasmodium falciparum is most common, mainly remote and tribal regions that carry a large share of the malaria burden. To prepare for vaccine rollout, it is important to start building the necessary policies and systems now. This includes identifying high-risk districts through strong disease tracking, planning for the vaccine within the existing immunisation system, and ensuring that cold storage facilities are available even in the most remote locations.

What innovations—whether digital, diagnostic, or programmatic—are you most optimistic about in helping India eliminate malaria by 2030?

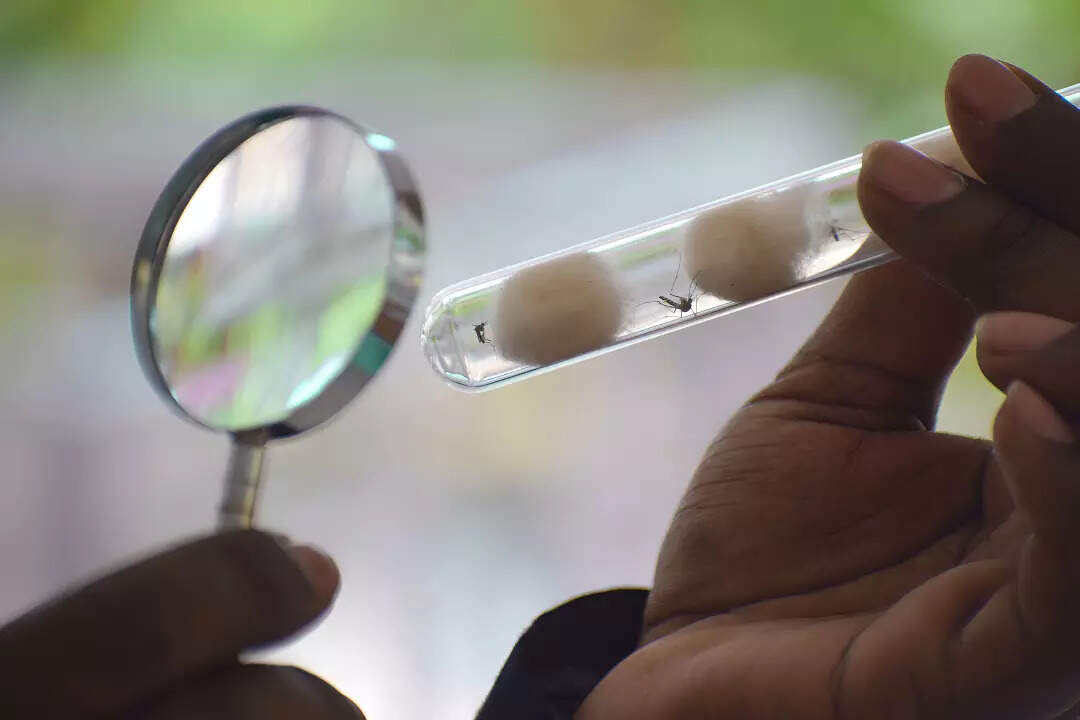

Programmatic innovations are crucial to eliminating malaria by 2030. Strengthening disease surveillance with advanced technologies will provide more accurate estimates of the malaria burden, support informed decision-making, and enhance risk prediction. Developing new methods of vector control and personal protection will complement current strategies, improving their effectiveness and sustainability. Through genome mapping of mosquitoes, Tata Institute for Genetics and Society (TIGS) has identified over 3,000 previously uncharacterized genes linked to insecticide resistance and parasite transmission. Leveraging this data, TIGS is developing gene-drive technologies aimed at rendering mosquitoes incapable of transmitting the Plasmodium parasite, thereby reducing malaria incidence without harming ecosystems. This innovative approach exemplifies how precision science can be harnessed to address public health challenges in an environmentally conscious manner. Additionally, improving logistics and ensuring the quality of malaria treatments and diagnostics will ensure their consistent availability. Timely detection and diagnosis in both high and low-endemic regions, supported by rapid diagnostic tests and mobile platforms, will be key to preventing further spread.

[ad_2]