[ad_1]

The treatment of kidney stones could soon be getting much faster, easier, and safer. Scientists have devised a method of non-invasively tearing the objects apart, using what are known as “acoustic vortex beams.”

For several decades now, doctors have utilized a non-surgical technique called extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) to break up kidney stones so they can be passed with the urine.

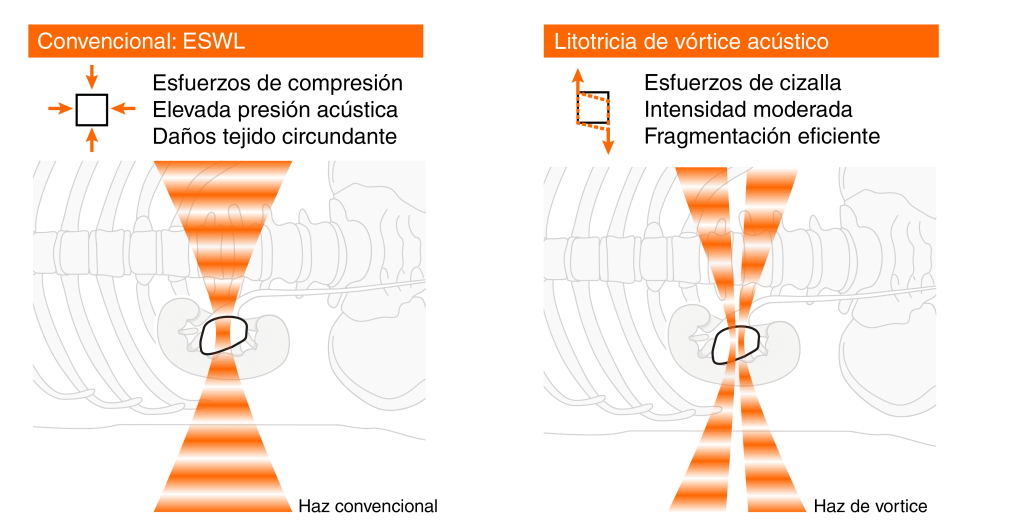

In a nutshell, the process involves subjecting the stones to high-intensity, externally applied acoustic pulses. While it spares patients from having to undergo surgery, they still typically must be sedated or even anesthetized, as the intense acoustic pulses can otherwise be painful.

Additionally, the procedure must be performed in a dedicated room using fairly large equipment. What’s more, the pulses may damage healthy tissue adjacent to the kidney stones. That’s where the new “Lithovortex” treatment comes in.

Currently being developed by scientists from Spain’s Universitat Politècnica de València (Valencia Polytechnic University) and the Spanish National Research Council, it utilizes a portable machine to generate swirling ultrasound waves known as acoustic vortex beams.

Instead of hitting the stones straight-on, as is the case with ESWL pulses, these beams spin around the stones like twister tornados. As they do so, they produce shear forces on the stones that cause them to disintegrate.

Spanish National Research Council

Importantly, because the vortex beams are so efficient at doing so, they only need to be half as strong as the pulses utilized in ESWL, plus they take half as long to get the job done. This means that patients don’t need to be sedated, there is very little risk of tissue damage, and the procedure can be performed in an out-patient clinic.

The machine (which is still in prototype form) utilizes a robotic arm to administer the vortices, which are generated by a piezoelectric transducer array. It’s guided by an accompanying imaging system.

Plans call for the Lithovortex system to be validated on an animal model sometime next year.

Sources: Universitat Politècnica de València, Spanish Research Council

[ad_2]